They called it the Bathysphere

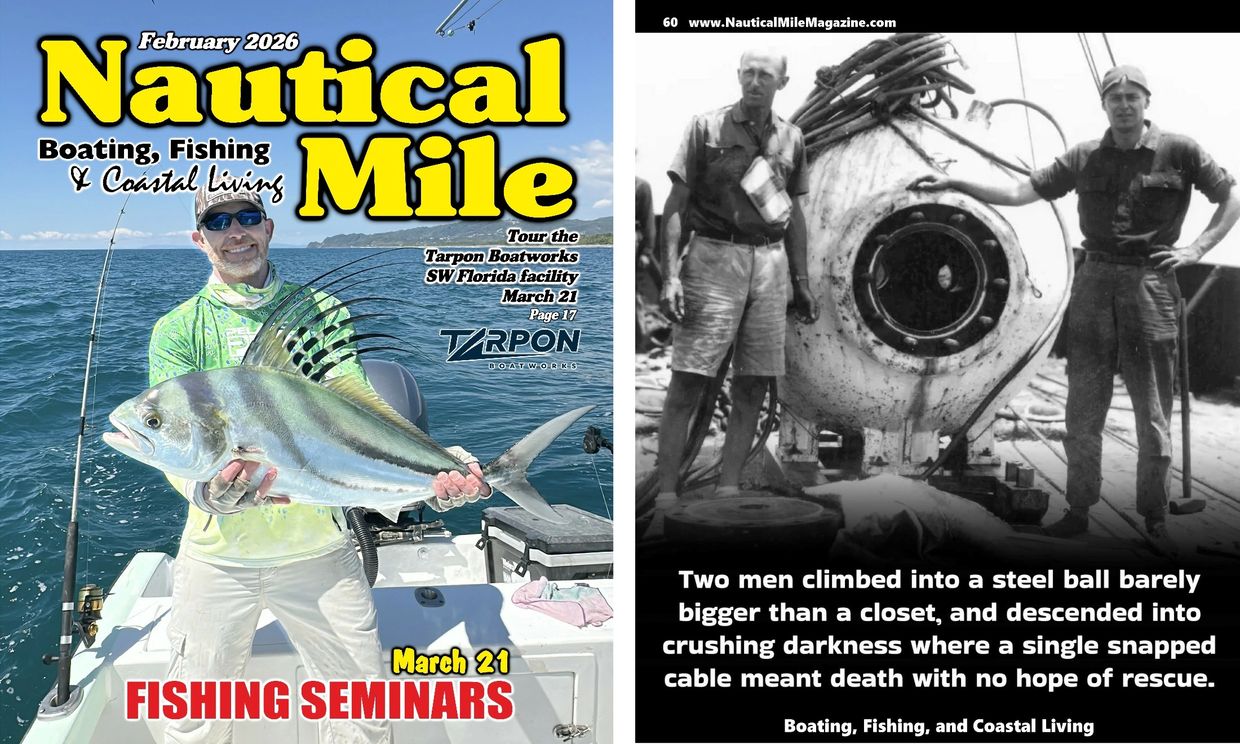

Two men climbed into a steel ball barely bigger than a closet, and descended into crushing darkness where a single snapped cable meant death with no hope of rescue.

The year was 1930. The place was the Atlantic Ocean off Bermuda. And William Beebe was about to become the first human to witness a world that had existed for millions of years but had never been seen by human eyes.

They called it the Bathysphere.

Imagine a hollow steel ball, just 4 feet 9 inches in diameter. Walls one inch thick. Just enough room for two grown men to crouch inside, knees pressed against chests, unable to stand or turn around.

One tiny quartz window 8 inches across is your only view to the outside world. No engine. No propulsion. No steering. Just a single steel cable attached to the top, connected to a ship floating on the surface.

That cable was everything. Your air supply ran through it. Your telephone line ran through it. And most importantly—it was the only thing preventing you from sinking endlessly into the abyss.

If it snapped, you were dead. No backup plan. No rescue possible. Just a long fall into darkness, followed by implosion when the pressure crushed the sphere like a tin can. This was Beebe's plan to explore the deep ocean.

In 1930, nobody knew what lived in the deep sea. The deepest any human had ever gone was maybe 60 feet while holding their breath. Past a few hundred feet, it was pure mystery—a vast darkness covering most of Earth's surface, completely unexplored.

Scientists theorized. They dropped nets and pulled up strange creatures. But nobody had actually seen what was down there. Nobody had watched these creatures in their natural habitat. Beebe wanted to change that.

On June 6, 1930, he and engineer Otis Barton—who had helped design the Bathysphere—squeezed inside the cramped sphere. Workers bolted the door shut from outside. Four hundred pounds of steel, sealing them in.

Through the tiny window, they could see the surface water—bright blue, warm, familiar.

Then the winch started lowering them down. The first few hundred feet were recognizable. Sunlight still penetrated. Fish they knew swam past. This was the world divers occasionally visited.

But then they passed 600 feet.

The light changed. Blue became dim purple. Then deep indigo. The familiar ocean disappeared, replaced by something else entirely.

At 800 feet, darkness swallowed them. Beebe pressed his face to the window, straining to see. The light from the surface couldn't reach this deep. It was pitch black—the kind of absolute darkness that doesn't exist on land, where there's always a moon, a star, a distant light.

Down here, there was nothing. Then, suddenly—lights. Not from above. From the creatures themselves. Strange fish drifted past the window, their bodies glowing with bioluminescence. Blues and greens and whites, pulsing and flickering like underwater stars. Beebe had never seen anything like it. Nobody had.

He scrambled to describe what he saw into the telephone, his voice transmitted up that fragile cable to scientists on the surface who wrote down every word: "A fish with fangs... transparent body... lights running along its side. Something with enormous jaws drifting past. Tentacles... glowing... can't identify the species..."

These weren't creatures from Earth—at least not the Earth humans knew. This was an alien world, right beneath the surface, that had remained hidden forever.

Every hundred feet deeper, the pressure increased. The Bathysphere's steel walls groaned under the force of millions of pounds of water pressing inward from all sides.

Beebe and Barton could hear it—creaks and pops as the metal compressed. Each sound a reminder that they were in a hostile environment where human bodies couldn't possibly survive.

If the sphere failed—if a weld gave way, if the window cracked—the water would rush in with such force it would kill them instantly. The pressure would crush their bodies before they could even drown.

But they kept going deeper.

1,000 feet. 1,500 feet. 2,000 feet. At every depth, new creatures appeared. Things with bodies too bizarre for names. Adaptations that made no sense in the sunlit world above.

Fish with jaws that unhinged to swallow prey twice their size. Creatures that were all mouth and teeth, built for a world where food was rare and you couldn't afford to miss a meal. Jellies that pulsed with internal light, drifting through the darkness like ghosts.

And the darkness itself—absolute, crushing, eternal.

Beebe later wrote: "The only other place comparable to these marvelous nether regions must surely be naked space itself, out far beyond atmosphere, between the stars." He wasn't in the ocean anymore. He was in space—but down instead of up.

On August 15, 1934, they made their deepest dive, 3,028 feet below the surface. Over half a mile of water pressing down on them from above. The cable stretched so far up they couldn't see the surface ship anymore—just an endless thread disappearing into blackness above.

At that moment, William Beebe became the first human to witness the true deep sea. Not the shallow coastal waters. Not the continental shelf. But the real ocean—the vast, dark, crushing realm that covers most of the planet and supports most of Earth's biomass.

He was the first to see it with human eyes. He later described it simply: "The first to look upon a new world."

Think about that for a moment. In 1934, humans had climbed mountains, crossed deserts, reached the North and South Poles. We'd mapped continents and sailed every ocean.

But we'd never actually seen most of our own planet.

The deep ocean was more unknown than the surface of the Moon would be decades later. And Beebe, cramped inside a steel ball suspended by a cable, was the first to open that door.

The Bathysphere had no backup systems. No emergency escape. If something went wrong—if the cable frayed, if the winch failed, if the sphere sprung a leak—there was no plan B. Death was one mechanical failure away at all times.

But Beebe went anyway. Not for fame. Not for money. But because the unknown demanded to be known. Because humanity couldn't claim to understand Earth while ignoring 71% of its surface.

Every descent was an act of extraordinary courage wrapped in scientific curiosity.

The Bathysphere made multiple dives between 1930 and 1934, each one pushing deeper into the unknown. After the record 3,028-foot descent, the technology was retired. Too risky. Too primitive compared to what would come later.

Today, submersibles have reached the deepest point in the ocean—nearly 36,000 feet down in the Mariana Trench. We have remotely operated vehicles that can explore places no human will ever visit in person.

But none of that diminishes what Beebe did.

He was first.

The first to see the alien glow of bioluminescent creatures in their natural habitat. The first to witness the crushing darkness of the deep sea.

The first to understand that Earth contained worlds we'd never imagined. He didn't have modern technology. He had a steel ball, a cable, and courage.

And that was enough to change human history. When Beebe returned from that final dive, he tried to explain what he'd seen. But words failed him. How do you describe a world so different, so alien, that nothing in human experience prepares you for it?

He wrote: "There came to me at that instant a tremendous wave of emotion, a real appreciation of what was momentarily almost superhuman, cosmic... I was privileged to peer out and actually see the creatures which had evolved in the blackness of a blue midnight which, since the ocean was born, had known no following day."

Read that again. "A blue midnight which had known no following day."

He'd visited a place where the sun had never shone. Where daylight was a myth. Where evolution had taken a completely different path in eternal darkness.

And he'd lived to tell about it.

The Bathysphere itself still exists. You can see it at the National Geographic Museum. A small, cramped sphere with a tiny window—hard to believe anyone was brave enough to climb inside and descend into the crushing deep. But Beebe did, multiple times.

Because some questions are more important than fear. Because some knowledge is worth the risk of death.

Because someone had to be first to open humanity's eyes to the vast, strange, beautiful darkness that covers most of our planet.

So here's the question that echoes across 90 years:

Would you have climbed into that steel ball? Knowing that a single mechanical failure meant death.

Knowing there was no rescue, no escape, no backup plan.

Knowing you'd descend into absolute darkness to see things no human had ever witnessed.

Would you have sealed yourself inside that tiny sphere and said: "Lower me down"?

Or would the fear have been too much? Beebe looked at the deep ocean—the most hostile environment on Earth—and chose knowledge over safety. Chose wonder over comfort. Chose to risk everything to see what was there.

That's not just exploration. That's courage in its purest form.

The deep ocean still holds mysteries. We've mapped more of the Moon's surface than our own seafloor. There are creatures down there we've never seen, ecosystems we don't understand, and questions we haven't even thought to ask yet.

But thanks to William Beebe, we know those mysteries are there.

Because one man climbed into a steel ball barely bigger than a closet and descended into the crushing darkness on a single cable.

And when he came back, he brought with him the knowledge that Earth was stranger, more beautiful, and more alien than anyone had imagined.

That's the power of one person willing to face the unknown.

So I'll ask again: Would you have dared?

______________________

Author unknown

Subscribe to Nautical Mile HERE:

Contact Nautical Mile:

Copyright © 2026

Nautical Mile Magazine

All Rights Reserved.